This material is available in other languages:

ru

26 Jun 2024

Lawyers of Memorial win ECHR case on access to Soviet archives

The court ruled that Russian authorities violated the article on freedom of expression

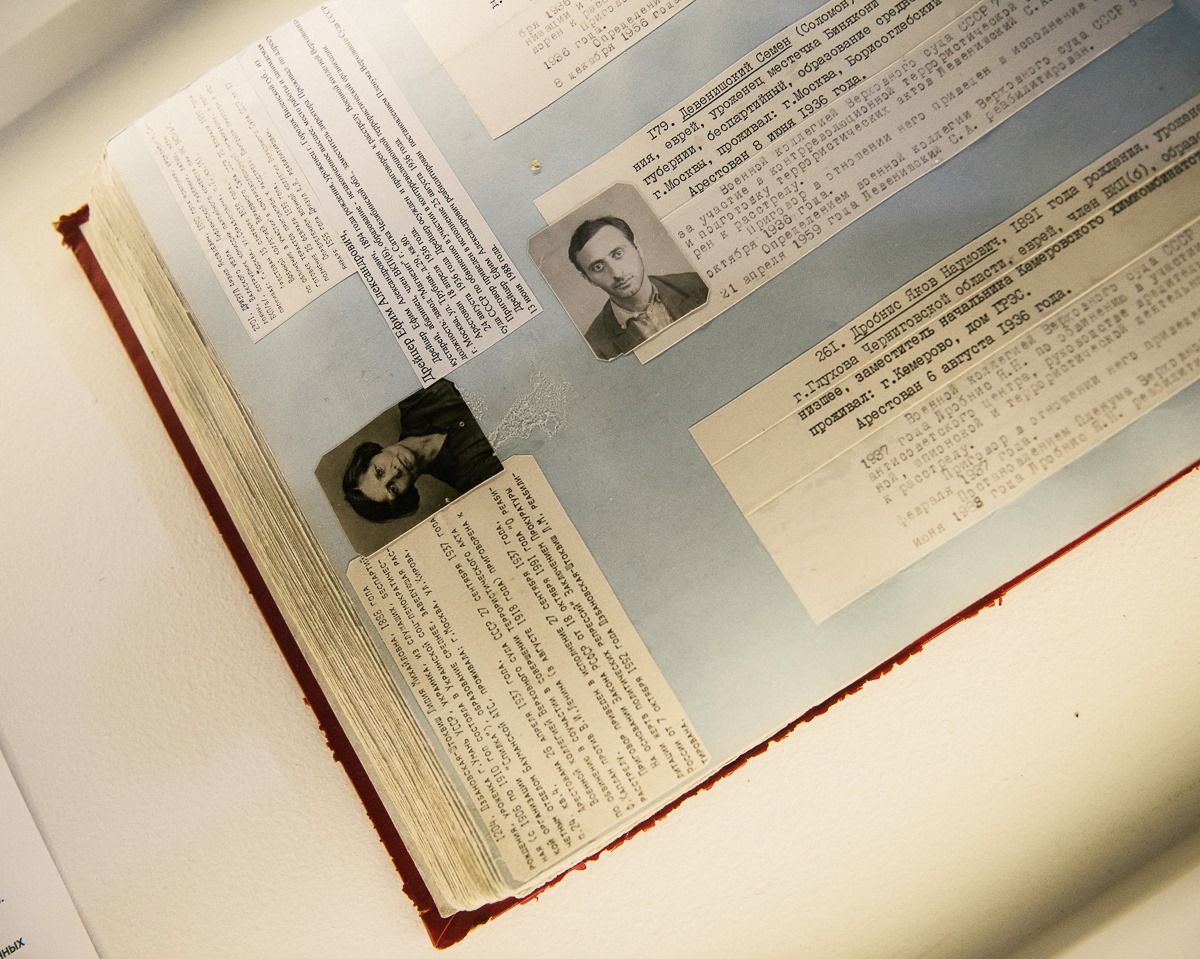

Photo: Lena Balakireva

Table of contents

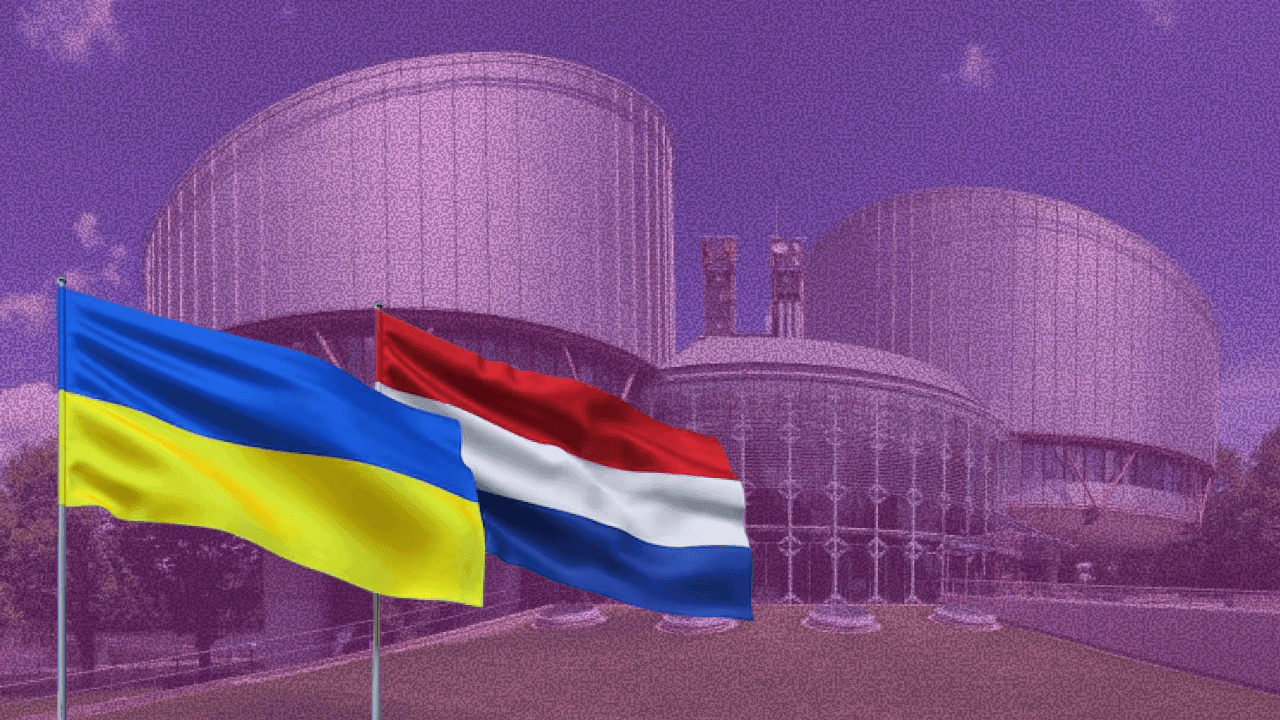

On June 18, the European Court of Human Rights issued the ruling "Suprun and Others v. Russia." It included several cases concerning the restriction of access to archival information related to Soviet political repressions. The ECHR ruled that the Russian authorities violated Article 10 on freedom of expression of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The ruling included the cases "Prudovsky v. Russia" and "International Memorial v. Russia." The complaints to the ECHR in these cases were filed by lawyers from the Memorial Center and an attorney collaborating with the Memorial Human Rights Center and International Memorial.

What happened

The Sergey Prudovsky's case

Sergey Prudovsky is a historian specializing in Soviet political repressions. He has published several books, including one detailing his grandfather's time in the Gulag.

Prudovsky specifically researched the NKVD's "national operations"—a series of mass repressive campaigns against foreign citizens and certain ethnic groups within the USSR, as well as ethnic Russians living abroad.

During one such campaign, the "Harbin operation," targeting former employees of the Chinese Eastern Railway and re-emigrants from China, 19,312 death sentences and 10,669 other punishments were issued.

Among these victims was Tatyana Kulik, who was sentenced to death as a Japanese spy and executed the next day. Prudovsky wanted to include her story in his forthcoming book on the "Harbin operation." In 2018, he approached the FSB in Moscow to request access to Kulik's case materials.

Prudovsky was granted access only to copies of the originals, with the positions, names, and signatures of NKVD officers and prosecutors involved in Tatyana Kulik's case redacted. The FSB justified this by citing the Interdepartmental Commission on State Secrets' decision to extend the confidentiality of some 1917-1991 information for thirty years, until 2044.

Prudovsky challenged the FSB's refusal to provide unredacted information, arguing that such information is not a state secret, as materials concerning human rights violations by state authorities and officials cannot be classified.

On June 4, 2020, the Moscow City Court rejected the historian's complaint, stating that information about NKVD and Soviet prosecutor's office employees reveals the identities of counterintelligence officers, which is a state secret. Subsequent courts upheld the initial decision.

Prudovsky also requested colored copies of 15 pages of archival documents from the FSB Central Archive for his book, particularly interested in records of prisoner transfers and execution reports. The Central Archive denied this request, allowing only document viewing in the reading room.

The historian challenged this refusal in the Khoroshevsky District Court of Moscow, but on June 7, 2020, the court rejected the complaint, ruling that only rehabilitated persons and their relatives have the right to free copies. Subsequent courts upheld this decision.

A similar situation occurred with Prudovsky in December 2019, when he requested access to archival criminal cases of former NKVD employees. He went to court again, but on July 20, 2020, the Khoroshevsky District Court, as well as subsequent courts, upheld the FSB's decision.

The International Memorial's case

In December 2019, International Memorial requested access to NKVD "troika" protocols from the FSB in Karelia, either to photograph the documents themselves or to obtain copies for a fee. Memorial was working on a documentary project about political repressions in the Republic of Karelia in 1937-38.

The FSB denied Memorial's request, stating that copies of documents could only be obtained in two cases: free of charge for rehabilitated persons and their relatives and for purposes related to social protection. International Memorial was allowed to view only the original documents.

International Memorial filed a complaint with the Petrozavodsk City Court of Karelia, arguing that the ban on copying unduly burdened their research. On June 17, 2020, the court found the FSB's refusal legal. Subsequent courts upheld the decision.

In July 2019, researchers from the Memorial Scientific-Information Center, along with International Memorial, requested information from the General Prosecutor's Office about 11 former prosecutors who were part of the NKVD "troikas." The General Prosecutor's Office denied the request, citing the Personal Data Law.

International Memorial appealed the refusal in the Tverskoy District Court of Moscow. The human rights activists argued that the requested information concerned official duties, not private life. Memorial also stated that restricting access to information about these prosecutors violated the right to freely receive and disseminate information about those involved in political repressions in the USSR.

On July 24, 2020, the court rejected the complaint, stating that the archival materials concerning the prosecutors contained details of their private lives. The court also claimed that there was no significant public interest in disclosing information about the prosecutors, as their membership in an illegal extrajudicial body was not convincing evidence of crimes against justice. Subsequent courts upheld this decision.

The ECHR ruling

In the ruling, the European Court recognized that the refusals to International Memorial and researcher Prudovsky were "interferences" with their rights. Regarding the substance of the refusals, the ECHR made the following conclusions:

1. Private life of a deceased person does not continue after death

The individuals about whom archival information was requested were professionally active in the 1930s and 1940s and had already died by the time of the request. Therefore, access to information about deceased NKVD officers or prosecutors from the Stalin era could not infringe on their private lives. However, Russian courts did not consider this factor.

2. Historians and human rights activists did not seek to expose intimate aspects of private life

Article 8 on the right to respect for private and family life of the Convention can protect the feelings of descendants, ensuring that their deceased ancestors are treated with respect. However, the applicants did not seek to expose intimate aspects of the private lives of criminals or victims of political repressions. Both Prudovsky and International Memorial wanted access to data related to public or professional, not private, lives of the participants—basic biographical elements, employment records, and details of extrajudicial proceedings. In this sense, the professional activities of former officials cannot be considered private life.

3. Access to archival materials could not harm state secrets or the authority of the judiciary

The ECHR points out that it seems unlikely that disclosing the names, ranks, and positions of individuals involved in fabricating criminal cases under the former regime more than 80 years ago could undermine modern national security.

In the late 1980s, the authorities declared the NKVD and its extrajudicial bodies unconstitutional and acknowledged their responsibility for mass human rights violations during the Great Terror. Therefore, there was no "pressing social need" to keep the quasi-judicial process secret for nearly 90 years.

The European Court notes that the historian's and human rights activists' research focused on state-sanctioned human rights violations, including ethnic deportations and executions, which were widespread in the 1930s and 1940s.

The pursuit of historical truth represents a fundamental aspect of freedom of expression, requiring a high level of protection, the Court summarizes. Interference with historical research on this matter inevitably creates the impression that the aim was to ensure impunity for those responsible for serious human rights violations.

4. Restrictions on access to archives did not pursue a legitimate aim

Archives and Russian courts justified the refusals by stating that the law explicitly does not allow providing copies to anyone other than rehabilitated persons and their descendants and does not permit making copies independently.

In the context of access to information, the ECHR has previously indicated that under the article on freedom of expression (Article 10 of the Convention), the law cannot allow arbitrary restrictions that may become a form of indirect censorship. While requests for copies of archival documents may be refused under certain circumstances, simply citing a legislative gap is insufficient to justify interference with the right to freedom of expression.

The ECHR notes that the documents were available for viewing, and the restriction was not necessary for the effective functioning of the archives. Besides the fact that manually extracting excerpts from documents took much time for the historian and human rights activists, it did not help them enhance the reliability of their work in the eyes of the public as much as copies of the original documents would. This limited the public's access to this information and undermined the possibility of public discussion on a socially significant issue.

The ECHR ruled that Russian authorities violated the freedom of expression article (Article 10 of the Convention) regarding the applicants. The Court awarded Sergey Prudovsky and International Memorial 7,500 euros each in compensation.